What we catch vs what we eat: Nutrition and sustainability in the UK blue food system

What we catch vs what we eat: Nutrition and sustainability in the UK blue foods system

Date posted: 2 February 2026

Why blue foods matter for sustainable diets

Blue foods are foods from aquatic environments, both marine and freshwater. These include finfish, shellfish (bivalves and crustaceans), and seaweeds and other aquatic plants, from sources of both wild capture fisheries and aquaculture.

Blue foods are often overlooked in sustainability debates, which tend to focus on meat, dairy, and plant-based alternatives (Costello et al., 2020). Yet seafood stands out for two reasons. Firstly, it is nutrient dense - oily fish are among the richest dietary sources of omega-3s (DHA/EPA), vitamin B12, and vitamin D (Bianchi et al., 2022). Secondly, most blue foods tend to have lower environmental footprints than most terrestrial animal proteins (Bianchi et al., 2022).

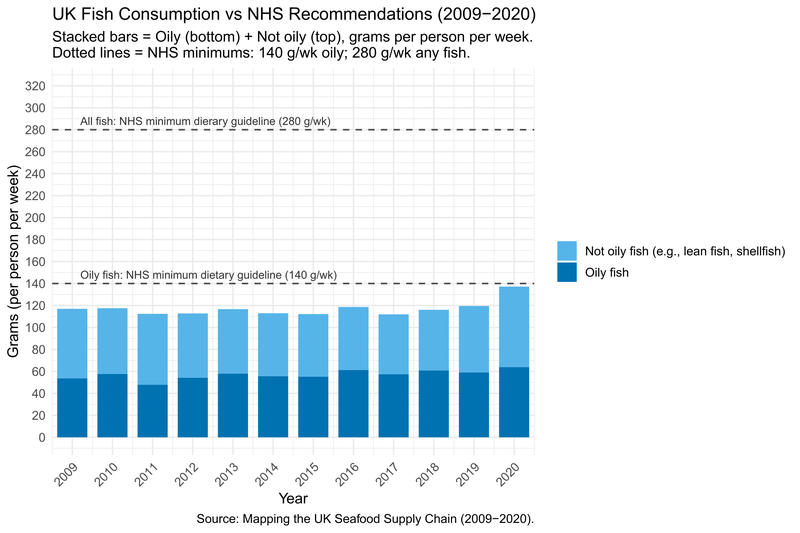

The NHS recommends consuming at least two portions of fish per week, one of which should be oily (The Eatwell Guide, 2016). Interestingly, fish (and vegetables) are the only food groups with specific UK dietary guidelines. This speaks volumes about their role in human health.

The UK context: what we catch vs what we eat

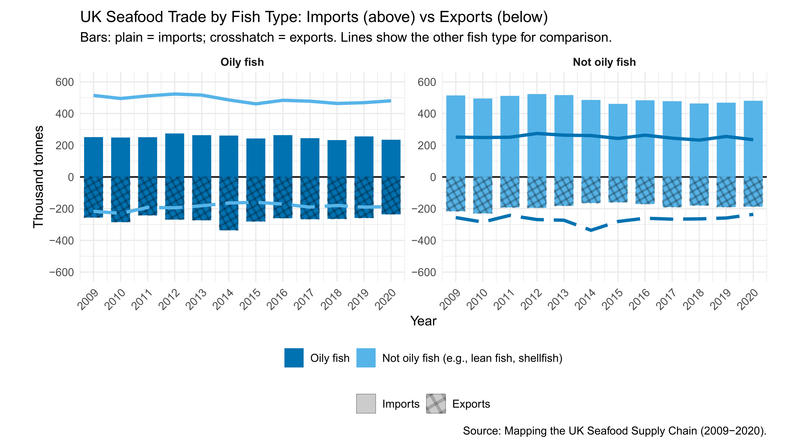

Despite being an island nation, the UK is far from self-sufficient in seafood. Around 80% of what we eat is dominated by just five species - cod, haddock, salmon, tuna, and prawns, also known as the 'Big 5' - most of which are imported (Harrison et al., 2023). Meanwhile, we export large volumes of nutrient-rich oily fish, such as mackerel and herring, losing vital omega-3s, and vitamins B12 and D3 in the process (Löfstedt et al., 2025). Seafood trade in the UK reflects this imbalance: imports are dominated by the Big 5 and other non-oily fish, while oily fish - despite their nutritional value - are exported in significant quantities (see Figure 1). These flows fit a global picture in which trade and distant-water fishing - where fleets from one country harvest fish in the waters of another or in international waters - shape who gets nutrients from the ocean, often widening disparities between countries (Nash et al., 2022).

Figure 1: UK seafood imports and exports by fish type (i.e. oily and non-oily blue foods) between 2009 and 2020.

Barriers and opportunities

Why don't we eat more diverse and locally-caught fish? Preferences, price sensitivity, and low cooking confidence keep diets narrow (Harrison et al., 2023). Cultural association of fish with traditional takeaway dishes, alongside perceptions of being complex or time-consuming to prepare, further constrain consumer choices. These consequent demand patterns, more than supply constraints, are the primary drivers of our current trade and consumption (Löfstedt et al., 2025).

But there are also clear opportunities. There are several simple ways to close the UK 'blue foods gap' (Figure 2):

- Make affordable options the norm: canned oily fish and frozen options are cheap and convenient.

- Build skills and familiarity early: England's 'Fish in School Heroes' initiative (Food Teachers Centre, since 2019) gives GCSE students hands-on practice handling and cooking a range of species, deliberately beyond the Big 5, using fish donated by industry.

- Align policy and procurement: schools, hospitals, and prisons can prioritise locally-caught and farmed fish and bivalves, aligning menus with NHS guidance and UK net-zero goals.

- Labelling and marketing standards could be strengthened to clearly highlight rich omega-3 sources and verify low-carbon species, making healthier and low-impact options the easy default (Bianchi et al., 2022).

- Track nutrients in trade: incorporating nutrient-balance metrics in seafood trade assessments would help ensure the UK retains key nutrients instead of exporting high-value species and importing lower-nutrient products (Bianchi et al. 2022)

UK seafood consumption between 2009-2020. The dotted line shows the UK dietary guideline for fish consumption

Looking ahead: climate change and blue food supply

Climate change will shift where blue foods are produced and who receives the associated nutrients. Globally, reforms and innovation could increase output - sustainable mariculture and better management together can increase supply (Costello et al., 2020). Critically, improved utilisation and management could sustainably double nutrient yields from capture fisheries, meaning 'enough fish in the sea' depends on how we manage and use what we catch (Cardinaals et al., 2023). Yet climate change is projected to worsen nutrient inequalities, with tropical, lower-income countries losing the most nutrient access unless policy adapts (Cheung et al., 2023).

For the UK, practical steps include eating more locally-caught oily and shellfish, supporting low-impact mariculture under robust standards, and ensuring trade and procurement protect domestic nutrient availability while avoiding offshoring impacts (Costello et al., 2020; Cheung et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Seafood is not the single solution for sustainable diets, but an underused opportunity. UK intake falls short of NHS guidelines, and we export much of our most nutrient-rich fish. The solution blends informed choice and policy design: making oily fish easy and affordable, diversifying beyond the Big 5, and aligning procurement, labelling, trade, and fisheries management with public-health and climate goals. Together, these steps could improve human health and build more resilient food systems.

Eleanor Miller is a final year PPE student at Oxford, with experience in student sustainability work through her time as a sabbatical officer at Oxford SU. This blog was supported by her Crankstart Internship at the Oxford Martin School, where she explored the role of fish in sustainable diets, combining policy perspectives with data exploration in R. This project highlighted the complex realities of food systems - from trade policy to cultural habits, from health to climate models. For her, as a PPE student, it has emphasised the importance of the political economy in shaping even the food on our plates.

References:

1. Bianchi, M. et al. (2022) Assessing seafood nutritional diversity together with climate impacts informs more comprehensive dietary advice. Communications Earth & Environment 3(1), p.188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00516-4

2. Cardinaals, R.P.M et al. (2023). Nutrient yields from global capture fisheries could be sustainably doubled through improved utilisation and management. Communications Earth & Environment 4(1), p.370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01024-9

3. Cheung, W.W.L. et al. (2023) Climate change exacerbates nutrient disparities from seafood. Nature Climate Change 13(11), pp.1242-1249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01822-1

4. Costello, C. et al. (2020) The future of food from the sea. Nature 588(7836), pp. 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2616-y

5. Harrison, L.O.J. et al. (2023) Widening mismatch between UK seafood production and consumer demand: A 120-year perspective. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 33(4), pp.1387-1408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-023-09776-5.

6. Löfstedt, A. et al. (2025) Seafood supply mapping reveals production and consumption mismatches and large dietary nutrient losses through exports in the United Kingdom. Nature Food 6(3), pp. 244-252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01102-x

7. Nash, K.L. et al (2022) Trade and foreign fishing mediate global marine nutrient supply. Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences 119(22), p. e2120817119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2120817119

8. The Eatwell Guide (2016) The Eatwell Guide - Helping you eat a healthy, balanced diet. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5ba8a50540f0b605084c9501/...

9. The Food Programme (2024) Fishing for change. The Food Programme, BBC Radio 4. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0024p2q